This essay is a departure from my usual Monday Morning Note. It was first published in 3 Quarks Daily, and appears here after a weekend of nationwide protests against the Republican administration. It offers a positive nonpartisan approach to the corruption introduced into our politics by big money.

And these two [the rational and spirited] will be set over the desiring part—which is surely most of the soul in each and by nature the most insatiable for money—and they’ll watch over it for fear of its…not minding its own business, but attempting to enslave and rule what is not appropriately ruled by its class, thereby subverting everyone’s entire life. —Plato’s Republic 442a

At a time when many of us are casting about for ways to resist the corruption and authoritarianism taking hold in the US and elsewhere, I offer here an idea for a tool that helps inform, direct, and scale consumer power on behalf of the common good. The tool would be a customized AI that’s free to use and accessible via an app on smartphones. I’m surprised it doesn’t already exist.

Before explaining how this could work, let me say why I think we should focus more on consumer power. By now it is evident that politics in the US has largely been captured by monied interests—foreign powers, billionaires, corporations and their wealthy shareholders. Thus in order to change the country’s social and political priorities we will need to encourage corporations and the wealthy to change theirs. Without their cooperation, it will be nearly impossible to change the political environment, since they play a decisive role in policy-making and election outcomes.

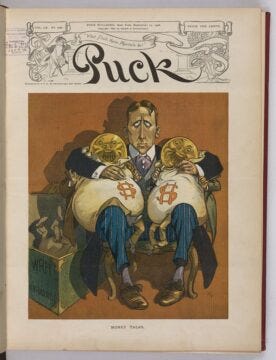

Socrates notes in the Republic that “money makers”—which expresses capitalism—operate in society much as the appetitive part operates in our individual souls. This grasping part of us seeks acquisition and gain; it wants all the cake, and wants to eat it too. If unregulated, this part (personified in Donald Trump) acts selfishly and tyrannically, grasping for more, bigger, better, greater everything—and subverting the common good in the process. In individuals, our unregulated appetites are expressed in addictions to screens, food, sex, alcohol, etc. In society, common goods like democracy, the rule of law, and clean air and water are undermined by the unregulated appetites of the money-maker class.

The solution, as Socrates saw, is not to punish or vilify this part, anymore than we would our child for wanting to play video games all night long. Instead, we need to restrain this element of our society, as we do our children. We do this by engaging the spirited (socially minded) and rational parts of our soul and society. These parts recognize the justice and goodness of sharing the cake, not least because it serves everyone’s interest to be cooperatively minded. The AI I envision will have this nonzero mindset baked into its operating constraints. Before turning to these, however, let’s see how powerful aggregated consumer spending can be.

Scaling Consumer Power

On May Day I canceled our Amazon Prime membership. I was inspired by seeing how one of our prominent money-makers, Jeff Bezos, “folded like the laundry” (as a clerk at the local hardware store put it) when Trump called him out for planning to let customers see what tariffs add to the price of items. Bezos had already forced the Washington Post to adopt his editorial policy, for no better reason than that he owns it. The policy change served his interests, which was to bend the knee to his likely master, Donald Trump.

A few people canceling Amazon Prime won’t bring bad actors like Amazon and Bezos to heel. But if as many people as voted against Trump (75,017,613)) in 2024 canceled their Prime subscriptions (at $139/year), Bezos would feel it, to the tune of $10,427,448,207. That’s a 10.5 billion dollar loss in one year. (The current number of Americans with Prime memberships is over 180 million.) Comparable leverage could be used to incentivize big players in media, gas and oil, chemical, transportation, defense, banking, crypto, retailing, pharmaceutical, health care, telecommunications, and tech sectors.

How the AI App Would Work

Imagine an app that provides a simple speech or text interface. The AI would be an ultra-knowledgeable maven offering real-time guidance on where best to spend your money. For example, at one intersection in our town there are three gas stations. Like the majority of Americans (67%), we favor transitioning to renewable energy. But we still own a gas-powered vehicle. The AI could answer the question I’ve been too lazy to research: ‘Which of these three companies is doing the most to transition to renewable energy?’ Or, if your personal priority was encouraging fair labor conditions, you could ask the AI, “Which of these companies offers employees the best working conditions and compensation?” possibly getting a different recommendation. Within limits, the AI’s response reflects your priorities.

Later, you can return to the advice and follow links, inspecting what data the AI drew on to reach its conclusion, educating yourself and confirming reasons to trust the AI. You might learn that one company has heavily invested in solar and geothermal, while another has spent huge sums lobbying against legislation that would support transitioning to renewable energy. In other sectors, the AI could help you learn what online platforms to use for gaming and streaming, where to get insurance and bank, what make of car to buy or airlines to fly, and so on. The AI’s transparency concerning data sources, how it weights them, what trade-offs it makes between competing values (and why), will be essential to establishing the trust necessary for mass adoption.

Until now we haven’t had the computational power for gathering information, analyzing data, and disseminating actionable real-time results to the majority of people in the country, or the planet. But now we do. Just about anyone with a smart phone (roughly 60-70% of the global population) could have access to this tool.

I’m sharing the broad contours of this idea, hoping to inspire others who have the practical competence to build it. There are many devilish details to sort out. But as Socrates warned, we shouldn’t let the ideal be the enemy of the good. In the spirit of making a good-enough tool, I imagine the AI starting as simple and limited, and evolving over time. After all, that’s what intelligent systems do. In the beginning, perhaps only a few critical business sectors fall within its scope of competence. Among my candidates for the most urgent to address are the tech, energy, and media sectors. The capability of this AI will increase rapidly, assuming that we can solve difficult problems like persuading the monied interests to allow the AI to develop using infrastructure they currently own. (I’m not just talking about AI companies. Bezos’s Amazon Web Services owns 31% of the global cloud infrastructure.)

Tunings and Constraints

First of all, the AI would be tuned for collaboration and cooperation. It will recognize but not engage in competitive, Machiavellian, zero-sum games. Its privileging of nonzero-sum strategies is a crucial differentiating feature from tools like boycotts. These have their place, but they perpetuate the zero-sum, us-and-them tribal mindset that is destructive of the common good.

Like Socrates, or like a good therapist for that matter, the AI would offer reframes that minimize divisiveness and maximize collaboration. If I asked it how best to hurt a company that I viewed as a bad actor, it might respond by asking what positive value and common good I seek. Depending on my answer, it would help me find the better actors, and give them my attention and business. In this way the AI would encourage users to shift to the nonzero-sum mindset—to think in terms of empowering good actors rather than punishing bad ones. It would tell me which booksellers, streaming services, music stores, and other businesses are more aligned with the common good than Amazon is. Obviously, making the switch will sometimes mean paying more—being in an economic position to tolerate more inconvenience and expense. (This is another of those details that need to be sorted out.)

Second, the AI would be proofed against being co-opted by political parties, partisans, and monied interests. Everyone can use the tool, and interest groups could encourage their supporters to use it, but no one should be able to game it. AI potentially has more capacity to resist corruption than humans because its sole motive is to offer the best counsel based on its core operating principles. An AI’s process would be more transparent and harder to co-opt than a government agency, think tank, or nonprofit, all of which are populated by human beings, who are vulnerable to social pressure, financial incentives, or changes in personnel. It cannot be tempted, for example, to change its advice because a money-maker makes a large donation in the hope of greenwashing its reputation. The AI will deliver results based on actual data concerning corporate behavior and its impact, not results influenced by donations, advertising dollars, and other payouts.

Third, the AI would offer advice based on the most accurate information available. It would draw from verified data sources, including scientific research, government statistics, corporate financial disclosures, third-party audits, and independent watchdog reports. Using the best, most vetted sources is crucial if users are to trust the AI’s advice. Here again, the devil is in the details of finding, supporting, and protecting good data sources. This is hard because monied interests increasingly exert disproportionate control over these. The republicans under Trump, with the support of corporate actors such as Musk, are doing enormous damage by attacking institutions and spreading disinformation. Their strategy includes preventing the collection of data, as the republicans have done with NOAA, among other agencies. As bad as all this is, AIs can excel at helping us recognize basic errors of fact and reason as well as Machiavellian attempts by money-makers to manipulate both.

Finally, this AI would be built and maintained by a small well-funded group of individuals who subscribe to a few core principles. (A money-maker like Bill Gates who professes interest in the common good could fund this project in perpetuity without diminishing his net worth—$115 billion—by even 1%.) There are some core principles the majority of citizens can acknowledge as common goods: Democracy. The rule of law. Free and fair elections. Individual rights. Clean air and water. Sustainable energy. Evidence-based reasoning.

In the Venn diagram of life, there is substantial overlap between my good and yours. If we can govern the monied interests, the common good will become more evident. The appearance of disagreement and division owes more to the way our common interests have been warped and weaponized by money makers and media platforms that propagandize citizens—on the left and right.

The technology exists to help consumers scale their power to influence the money-makers, and in turn the social and political order. What’s needed are the builders—technologists, philanthropists, and institutions willing to create and promote tools like this, tools that can help rebalance power between individual citizens and corporate ‘persons.’ As Socrates (and common sense) teach us, it’s better when the rational and socially spirited parts of ourselves and society step up and govern the appetitive part, which otherwise runs amok.