To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity and trust. -Henry David Thoreau

Some patients seek me out because I have a PhD in philosophy and had been a professor before becoming a psychotherapist. I always ask what makes this background attractive, and the answers fall along one or two lines. Some imagine I’ll somehow be more likely “to see through the bullshit to what’s really going on,” as one man put it. Others believe philosophy offers more depth and clarity on the big questions about the meaning and value of human life (and by extension their personal life) than they are likely to get from psychology. They’re right about this second point, though it is unlikely to come into therapy in the way they imagine. But I’m skeptical about the first assumption.

It is true that a philosopher will be good at seeing through bullshit—if it takes the form of an untenable philosophical position or a logical fallacy. But whatever a patient may think, such heady “bullshit” is rarely what actually leads them to seek therapy. Take the man who imagined I’d be helping him by calling out his bullshit. It turns out he has a hypercritical father who habitually chastised and corrected him when he was growing up. And guess what? It was not my philosophical training that helped me surmise something like this might be going on, and thus helped me avoid compounding his suffering by enacting the familiar role his father had played. I’ll come back to his story in moment.

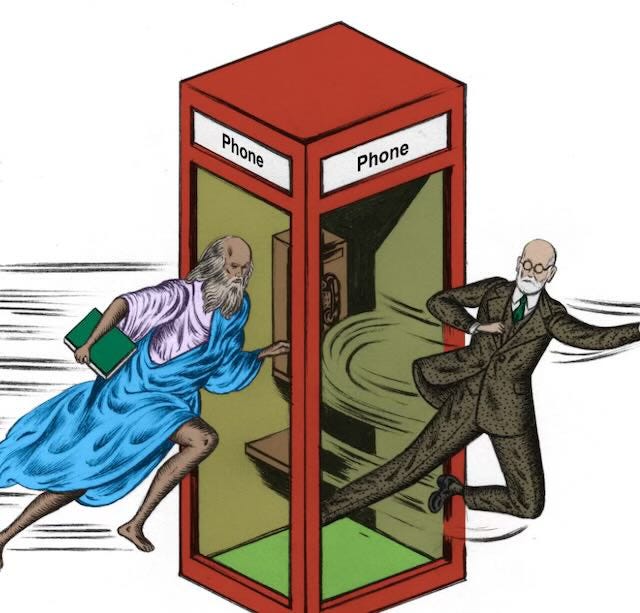

I am inspired to think about all this by a recent article in the New Yorker, entitled When Philosophers Become Therapists: The philosophical-counselling movement aims to apply heady, logical insights to daily life. The article offers a look at the guiding spirit of this growing movement. Reading it stirred up some thoughts and concerns, a few of which I offer here, using the article’s misleading (and revealing) title as a starting point.

But first let me say, enthusiastically, that philosophy can be of great value to therapists and other helping professionals. After all, one of my motivations in these notes is to offer my fellow allies a chance each week to think more broadly and philosophically about what we’re doing when we seek to be helpful. So I welcome this growing movement to emphasize the practical value of philosophy. Moreover, I think there is a place for philosophical counseling. Indeed, I am a member of the American Philosophical Practitioners Association (APPA), one of the main organizations offering certification in philosophical counseling.

So, why do I say the article’s title is misleading? Because what philosophical counseling offers is not therapy, and it is both confusing and potentially harmful to suggest otherwise. The three-day certification in philosophical counseling offered by the APPA is open only to those who have an MA or PhD in philosophy; no background in therapy is necessary. The course does not help philosophers become therapists. Rather, it teaches them how to make philosophical ideas practically valuable and accessible to non-philosopher clients seeking to broaden their thinking and perspective on life. The training includes an ethical code and how to screen for appropriate clients—including screening out those who have significant mental-health challenges.

I don’t know whether she means to, but Lydia Amir, the philosophical counselor profiled in the article, neatly captures why this counseling is different in kind from psychotherapy. Good therapists are deeply attentive to feeling and thinking, and are skilled listeners and empathizers. In contrast, Amir says of philosophical counseling that “it’s about thinking. It’s not developing skills of listening and being empathic, which philosophers are not especially trained to do. It’s personal tutoring in philosophy.” There is, she claims, “no other discipline that teaches you how to think better when it relates to your life.”

I agree with her, as long as we add that thinking alone is almost never sufficient to relieve suffering and promote flourishing. (Believe me, I’ve tried!) The danger is that the philosopher-counselor and/or their client won’t recognize just how different from therapy what they’re doing is, and why in many cases clients won’t get the help they need. Psychotherapy aims to help patients discover who they are, not tutor them in who Nietzsche or Sartre thinks they are, or should be. In this respect, we therapists are not tutors but the ones being tutored by our patients. Our primary virtue is not speaking but listening, not offering what we know but seeking to understand what the patient is telling us—through their thoughts, feelings, body language, behaviors, dreams, and so on.

Before training to become a therapist, I’d likely have taken my patient at his word when he told me he was looking for someone to call out his bullshit. I’d have been the more tempted because he is an educated, very intelligent man; so his request flattered me inasmuch as it suggested he thought me his equal or superior. But because of my training, I knew to ask why he was attracted to my philosophical background. And I was alive both to how I might be flattered and to the implicit self-aggression in his answer—I’m so full of shit it’s causing me to suffer. In time I was able to help him get curious about where this was coming from. (I should add that we never talked about philosophy.)

A key part of my therapeutic training has been to shift me away from my philosophical and teacherly habits. Instead of being their teacher, I am a student of my patients. Instead of preparing to speak, I prepare to listen. Instead of thinking what my patients need is what I’ve gleaned from great thinkers, I think what they most need from me is skillful empathic presence that encourages exploring and getting to know themselves in the context of our unfolding relationship. Instead of assuming that the meaning we’re seeking is explicit and propositional, I assume it’s often implicit and unconscious. As I did with my patient, I try to recognize when the explicit content is a defense against getting to know deeper, more unsettling things—like that the brilliant father he so admired might be the one who’s full of shit. Instead of assuming that my job is to help people think more clearly and deeply about ideas, I assume it’s helping people think more feelingly about their very personal lives.

Another thought provoking post. I’d read the New Yorker article previously. It had caught my attention as I consider myself someone who is practicing Stoicism and very interested in philosophy. But I came away a bit unsure what to think of the described philosophical counseling movement that was described. Your essay helped me connect the dots and better appreciate the strengths and weaknesses. And I was frankly a bit relieved when you described your own psychotherapy practices. My favorite part was the text at the end about listening. So lovely. As a former educator, maybe I too was a “help professional”. It often felt that way for sure. And I learned to advise new educators regarding their students, “Listen first. Don’t judge. Don’t react. Don’t get defensive. Don’t start forming a response in your head. Just listen, and maybe ask some questions. Listen to understand.”

Gary, I keep returning to this note while making my way through my MA program in clinical mental health training. I'd like to push one pressure point. Though he certainly talks more than a therapist should, I cannot help but continue to judge that Plato's Socrates gives a therapeutic model. Socrates is a midwife. If your schema is inconsistent and you do not see this, if a value is fuzzy and potentially harmful and you do not see this, Socrates uncovers and shows it to you. Socrates does not tell you what to think; rather, he makes apparent to you what is dispositional ("automatic") for you and helps you test it. I rather doubt most clients in need of healing would benefit from seeing Socrates himself (at least Plato's). While he exercises irony and certainly gives support, the challenging is much more prominent. Nonetheless, what Socrates maybe does do—and this is a real benefit of philosophy—is to help you recognize your deepest organizing principles and to get conceptual clarity about what they are. I always recoil when I see what CBT does referred to as "Socratic questioning." As it tends to get practiced, CBT does nothing of the sort (and it must fall short: CBT is not a way of life; Socrates is a eudaemonist). The question I keep coming back to: once rapport and trust are established, what if CBT or other orientations did? Socrates does not tell you what Socrates thinks about you. Socrates tells you what you think about you and then helps you test it. And maybe this is helpful for some clients with some problems. I cannot imagine philosophy does not contribute greatly in helping a client work through axiological distress (e.g., what does it mean really to flourish [universal] and what would this look like for you [particular]). But then I have not yet started practicum. I'm going to find out soon enough!

I'll end an already too long, bloated reply. A major difference between philosophy and therapy is that philosophy is about the universal and therapy is about the particular. Philosophy does not aim at and perhaps cannot get at the individual in her particularity (I think there is a lesson in the Phaedo about the limits of philosophical consolation for the individual, but that's a long story). But getting to our naked, vulnerable affective particularity is precisely what therapy must do.