The map is not the territory, - Alfred Korzybski

Note: Readers who have been following my pieces on authenticity can find the most recent essay, The Feeling of Authenticity, published at 3 Quarks Daily.

Over the weekend Awais Aftab, Martin Greenwald, M.D., NilsWendel, MD, and I recorded a video Q&A. The DSM came up, of course. (The DSM-5 is a handbook used by mental health professionals to diagnose mental health conditions. I discuss its significance in an earlier post, Diagnosis and Human Experience.) I was reminded of a little book about the DSM-5 by two Jungian psychiatrists, Steven Buser and Leonard Cruz: DSM-5 Insanely Simplified: Unlocking the Spectrums within DSM-5 and ICD-10.

Buser and Cruz took on the challenging task of providing a concise overview of the DSM-5. (They have an updated edition for the DSM-5-TR, but for our purposes the original edition suffices.) In this note I offer an overview of their approach, including a defense of the value of such insanely cartoonish simplifications—in the form of advice for how to become a better reader. Stay with me here!

During my 15 years of teaching, I regularly offered students this advice for studying a book. It’s advice I wish someone had given me when I was in high school. It doesn’t matter how good a reader you are, this advice will make you a better one.

Here’s the advice in a nutshell. When you pick up a book for the first time, take 2-5 minutes to get an overview. Move quickly, aiming for familiarity, not understanding. Start with the title and author(s) bio. Scan the table of contents to see how the book is organized and what themes jump out. Thumb through the pages quickly, noting chapter titles, subheads, illustrations, and graphs. Scan the bibliography and index, paying attention to subjects and authors cited. Remember, move quickly—don’t get bogged down because something is interesting or confusing. Set a timer if you have to. After you’ve done this, take a short break. Then, sometime that same day, return to the book and start reading more carefully.

This overview is useful when want to learn and remember new material. I do it automatically with non-fiction books and long articles. I’ll come back to how this technique leverages what Heidegger called the hermeneutic circle.

Buser and Cruz’s book exemplifies this advice. They offer readers a sweeping overview of the DSM-5, orienting us to a long, complicated manual. Fractally speaking—a fractal being a pattern that recurs at different scales—this note applies the same principle to their book. In yet another fractal, the DSM itself is an even more insanely simplified attempt to identif and distinguish human maladies. So, with no further ado, here’s my overview of their overview of the DSM-5’s overview.

The authors are MDs who practice psychiatry and are engaged in Jung studies and publishing. They intend the book for

busy clinicians wishing to get a quick command of the various changes introduced in the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 (DSM-5). The audience for this book includes therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, physicians, residents in training, medical students, others in the mental health field, and interested laypersons. We make liberal use of cartoons and hyperbole in order to capture broad ideas….The authors hope that by presenting engaging cartoons that attempt to reduce complex ideas into easily remembered images, the process of transition from earlier versions of the DSM to the present one will be made easier.

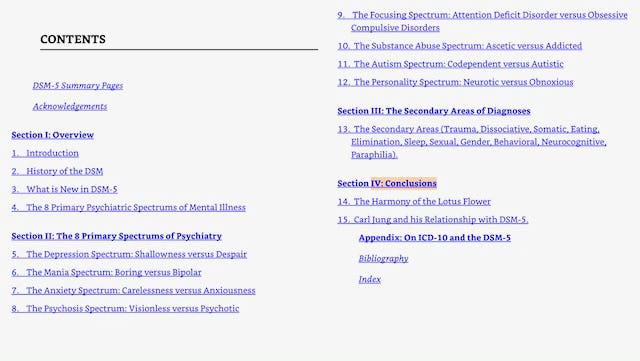

Here’s the Table of Contents

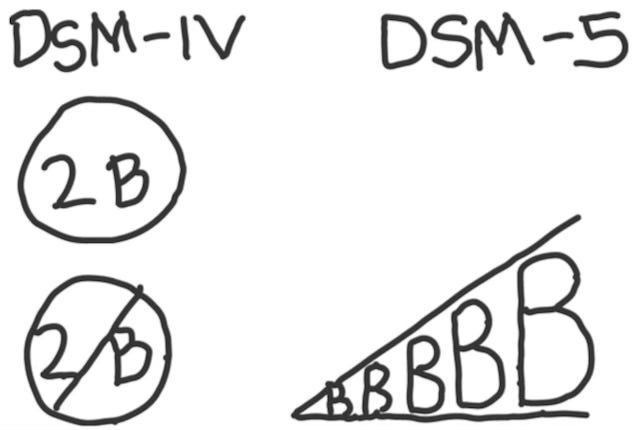

Here’s the organizing principle of their book, following the key change made by the DSM-5.

A major shift occurs with the introduction of DSM-5 that has broad implication for the way psychiatric illness is conceptualized. DSM-5 introduces the notion that illness exists along a spectrum or continuum rather than as an either/or phenomenon.

The DSM-5 planning groups established this idea from the outset, and throughout the manual the emphasis on illness as a spectrum is apparent. Also, the boundaries between certain disorders are less sharply defined in DSM-5.

The DSM-5’s cover illustrates this change.

Now for two powerful choices they made. They chose to organize their book around the idea of a spectrum. And they chose to have an eight-year-old, Luke Sloan, illustrate it. But doesn’t this undermine their credibility? To the contrary, it further establishes it, by making clear their cartoonish intentions: “Any attempt to simplify DSM-5 risks undermining some of the considerable work done to develop DSM-5. However, the DSM-5 speaks for itself; this guide is intended to enhance the usefulness of the DSM-5’s very rich content.”

My reading advice, to start with an overview, shares the assumption of their book: that you will go on to read and study the book! Overviews are not an alternative to careful reading. They are a powerful way to prime our minds: by getting an initial view of the whole, we acquire a frame in which to fit the parts we gather as we then read more closely.

As to the implications of moving from a categorial to a spectrum-based system of classification1

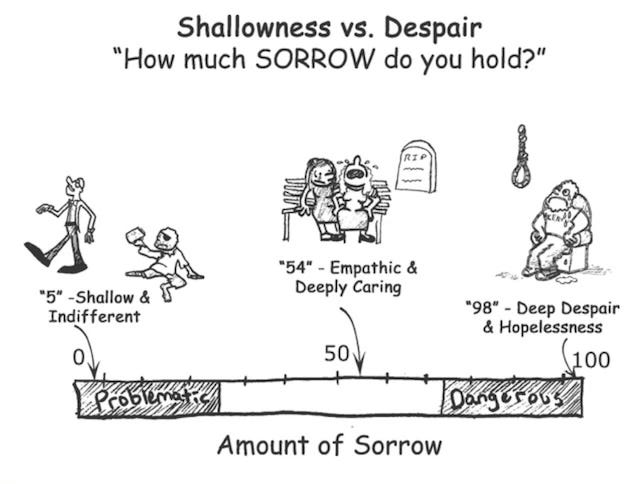

Everyone falls somewhere along the 8 spectrums. This conceptual model tends to destigmatize mental illness and strip it of shame. Just as the patient is located along a spectrum so are other people in their life. Everyone exists on a spectrum of severity or paucity of features. It may help to be reminded that we are all in this boat together.

Here are the 8 primary spectrums of mental illness. Each includes an illustration. I’ve provided two as examples.

The Depression Spectrum: Shallowness versus Despair

The Mania Spectrum: Boring versus Bipolar

The Anxiety Spectrum: Carelessness versus Anxiousness

The Psychosis Spectrum: Visionless versus Psychotic

The Focusing Spectrum: Attention Deficit Disorder versus Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

The Substance Abuse Spectrum: Ascetic versus Addicted

The Autism Spectrum: Codependent versus Autistic

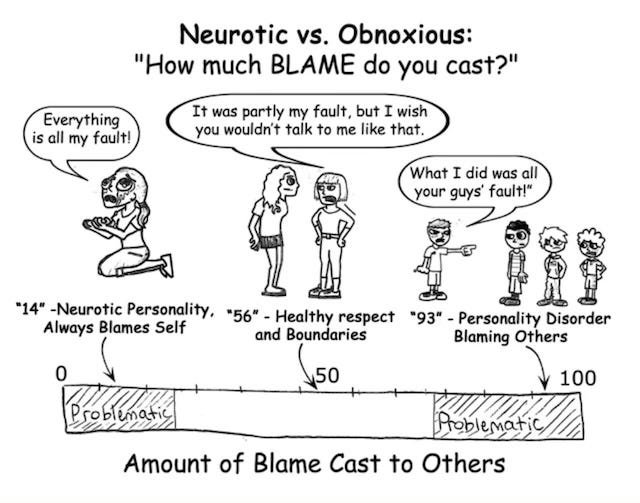

The Personality Spectrum: Neurotic versus Obnoxious

Their discussions link each of these spectrums to the DSM-5’s account. Below are some observations they make about personality disorders. These are notoriously difficult to define and treat. (Interested readers can check out Awais Aftwab’s recent post, which points out the not-insanely-simplified debate over how to understand and define personality disorders.) In any case, Buser and Cruz’s general description agrees with the experience of many clinicians.

A fundamental feature of personality disorders is the tendency people with these disorders have to externalize blame or causation for their symptoms. Individuals who suffer personality disorder have problems conducting the daily affairs of their lives and often have problems relating to others.

When a pattern of problems repeats they interpret it as further evidence that others are to blame for their difficulties. This is the meaning of maladaptive. Clinicians may find such patient’s defenses to be almost impenetrable. It can prove helpful to keep in mind that their inability to recognize their own role in their problems and the turmoil that surrounds them is a pivotal feature.

Even when we disagree with some of their framework, that too can help deepen our reading, prodding us to go back to the original text, thinking more carefully about what is (and isn’t) there.

Finally, the authors boldly provide an image to accompany their overview.

The 8 spectrums are paired and joined together by a parabola whose apex comes together with the other pairs at the center of the flower. This spot at the apex of the parabola is the middle range of each of the 8 spectrums. This is the “sweet spot” that we try to attain for each continuum. On the periphery of the flower are the extreme ends of each spectrum. As there are 8 primary psychiatric spectrums there are 16 poles altogether, 2 for each spectrum.

Back now to the hermeneutic circle. The core idea is that our understanding of a text (hermeneutics means ‘the art of interpretation’) depends on a dialectic between the whole and parts: our understanding of the parts depends on our view of the whole, while likewise our understanding of the whole depends on understanding the parts. By analogy, what a liver or a neuron is cannot be understood without knowing the larger whole in which they’re functioning, nor can that larger whole (the body) be understood without knowing the role of the constitutive parts.

In Being and Time, Heidegger presents the hermeneutic circle as a model for how we understand anything, including ourselves. Understanding is an iterative process, a virtuous circle, whereby a deepening grasp of the parts leads to a deepening view of the whole, which in turn sheds further light one the parts. Whether it’s the DSM-5, Being and Time, or our own lives, there’s consolation in knowing comprehension takes time.

Yes, “dimensional” is more accurate (and conceptually powerful) than “spectrum,” as clinicians reading this will recognize. But remember, this is insanely simplified!

I think their spectrums are close, but miss the mark when compared to the empirically validated models (here I am thinking of the OCEAN/Big 5). Their neurotic vs. obnoxious spectrum, for example, actually breaks down into two discrete Big 5 categories that are independent from one another. Neuroticism (i.e. propensity to experience negative emotion) and Agreeableness (the need to have harmonious relationships with others). Likewise their anxiousness vs. carelessness, which is again probably the Big 5 Neuroticism and Conscientiousness.

Gary, do you know if their spectrums come from the world of experimental psychology, or are they just speculations on the part of the authors?

Wonderful overview! Love the health-as-middle of all the spectra as a final cartoon.